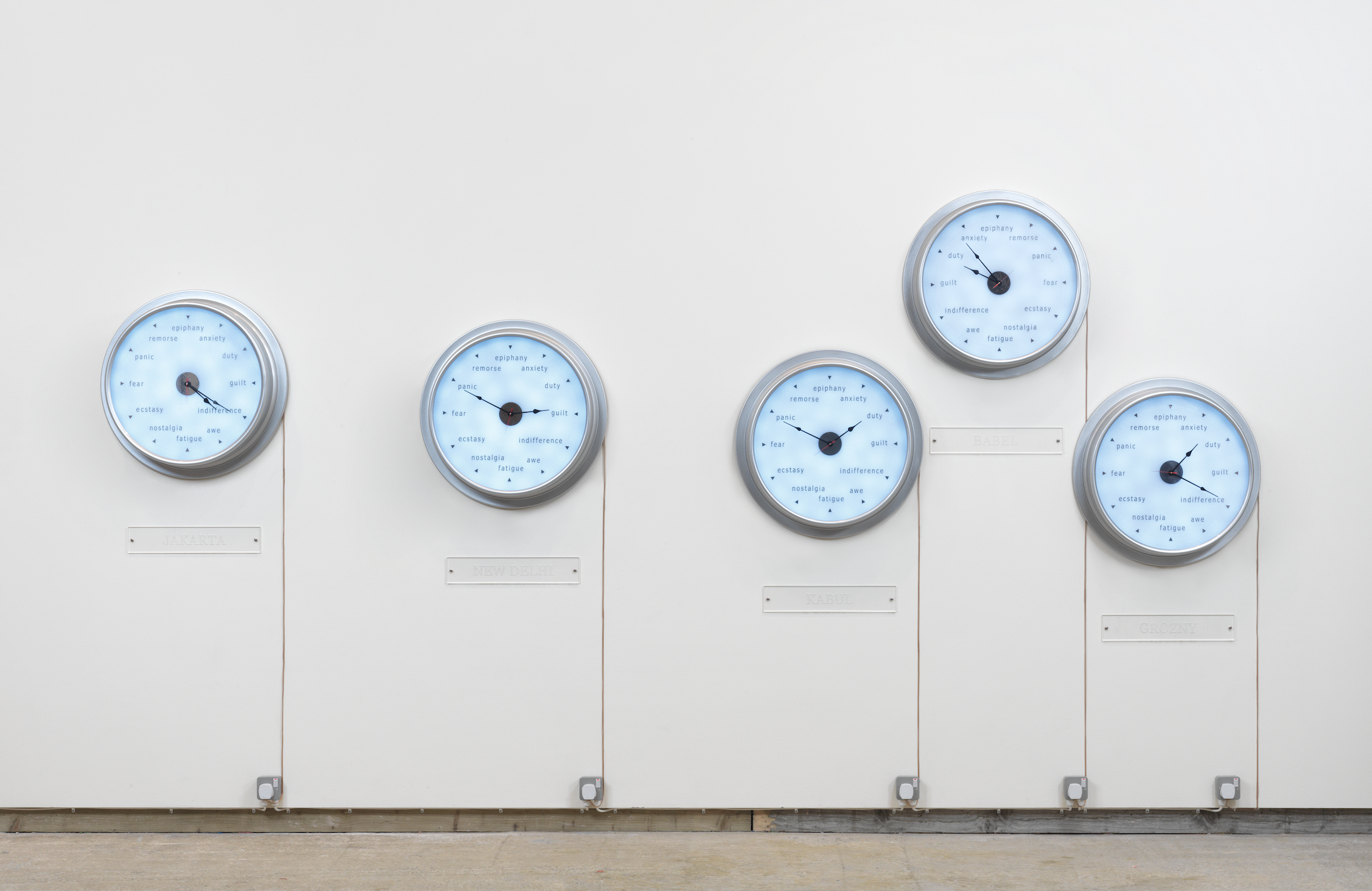

Escapement

Installation with 27 clocks, high glass aluminium with LED lights, four flat screen monitors, video and audio looped, dimensions variable

Frith Street Gallery, London (2009)

Escapement invokes clockwork, emotions, geography, fantasy and time zones to ask what is contemporaneity – what does it mean to be living in these times, in these quickening hours, these accumulating minutes, these multiplying seconds, here, now?

Escapement is a horological, or clockmaking term. It denotes the mechanism in mechanical watches and clocks that governs the regular motion of the hands through a ‘catch and release’ device that both releases and restrains the levers that move the hands for hours, minutes and seconds. Like the catch and release of the valves of the heart, allowing for the flow of blood between the chambers of the heart, which sets up the basic rhythm of life, the escapement of a watch, regulates our sense of the flow of time. The continued pulsation of our hearts, and the ticking of a clock, denote our liberty from an eternal present.

With each heartbeat, with each passing second, they mark here and now, promise the future and remember the resonance of heartbeat that just ended. It is our heart that tells us that we live in time.

Time girds the earth tight. Day after day, the hours, astride minutes and seconds, ride as they must, relentlessly. In the struggle to keep pace with clocks we are now everywhere and always in a state of jet lag, catching up with ourselves and with others, slightly short of breath, slightly short of time. Escape, when possible, is up a hatch and down a corridor between, and occasionally beyond, longitudes, to places where the hours chime epiphanies.

The installation invokes clockwork, emotions, geography, fantasy and time zones. Each clock face has twelve words that describe emotions, or states of being where we would normally expect the hours to be. When its a quarter past twelve, these clocks would read – ‘guilt past epiphany’. Twenty-four of the twenty-seven clocks mark the time of different cities – Liverpool, Baghdad, Delhi, Sao Paulo, Tokyo, Johannesburg and eighteen other locations. Three clocks tagged to three imaginary cities – Babel, Shangrila and Macondo – run backwards mirroring real time. The video screens show the face of an androgynous, ageless person, transiting between the hours, listening to heartbeats and other rhythmic and arrythmic sounds.

One Four Four Zero

Acrylic glass tubes in circular acrylic housing, 15 x 64 cm diameter

Frith Street Gallery, London (2009)

One thousand four hundred and forty crystal perspex tubes, some square, some circular, some hexagonal, sit tightly packed in what looks like an transparent empty clock set on a plinth. Each handcrafted perspex tube suggests the slot each minute takes up in the course of a day. Together, their jagged profiles add up to the suggestion of a dense urban skyline, a crystalline Hong Kong grafted on to Manhattan or Sao Paulo in somebody’s lucid dream. They are reminiscent of a cross section of the retina, crowded with the photoreceptor rods and cones that carry light signals from the eye to the brain. Deep within the recesses of the brain, the pineal gland reads the light that comes in and transduces light to synthesize and secrete melatonin, the hormone that communicates a sense of ambient time to the body. Sometimes, the conditions that people are compelled to inhabit – prolonged stretches of distortion in ambient light levels, irregularities in sleep and wakefulness, induced by transcontinental flights, overwork, pharmaceuticals or torture – lead to distortions in the somatic sense of time. Then, time is really out of joint, under our skins, in our bones.