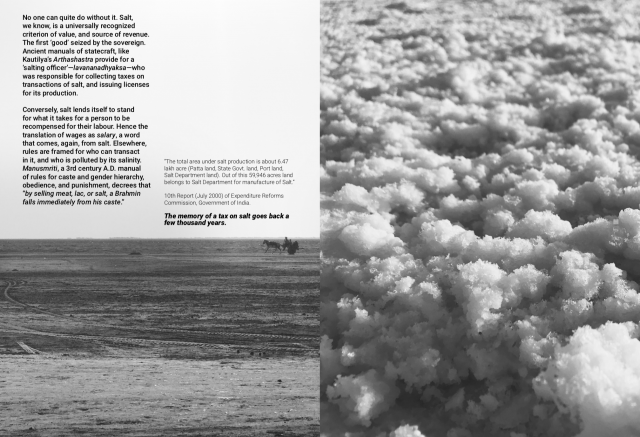

Raqs works with salt, or that refers to salt, as material or concept. The inquiry started from “Salt”, a photo-essay published in The Drama Review, Volume 65 Issue 4, 2021.

Salt, The Drama Review, Volume 65 Issue 4, 2021 (download)

A Planet Turns on its Axis Without Permission

Single screen, Video, 18:04 minutes

“Provisions for Everybody” at AV Festival, Newcastle (2018), ‘Still More World’ Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha (2019)

Turning, and turning around, on the Rann does not alter the white horizon. Salt– brilliant under the sun–dazzles the eyes, opens the lachrymal canals. We taste our own salinity as time seasons us.

The Little and Great Rann of Kutch stretch salt on the surface of the earth as far as the eye can see. They are earth that becomes sea, and sea that becomes earth, and land that turns to salt as it dries. Once the Rann of Kutch was a forest, with dinosaurs that are now fossils under the salt. Then, as the Arabian Sea made its claims on the shore, it became something like a marine drag queen, masquerading for half the year as land.

Tears (are not only from weeping)

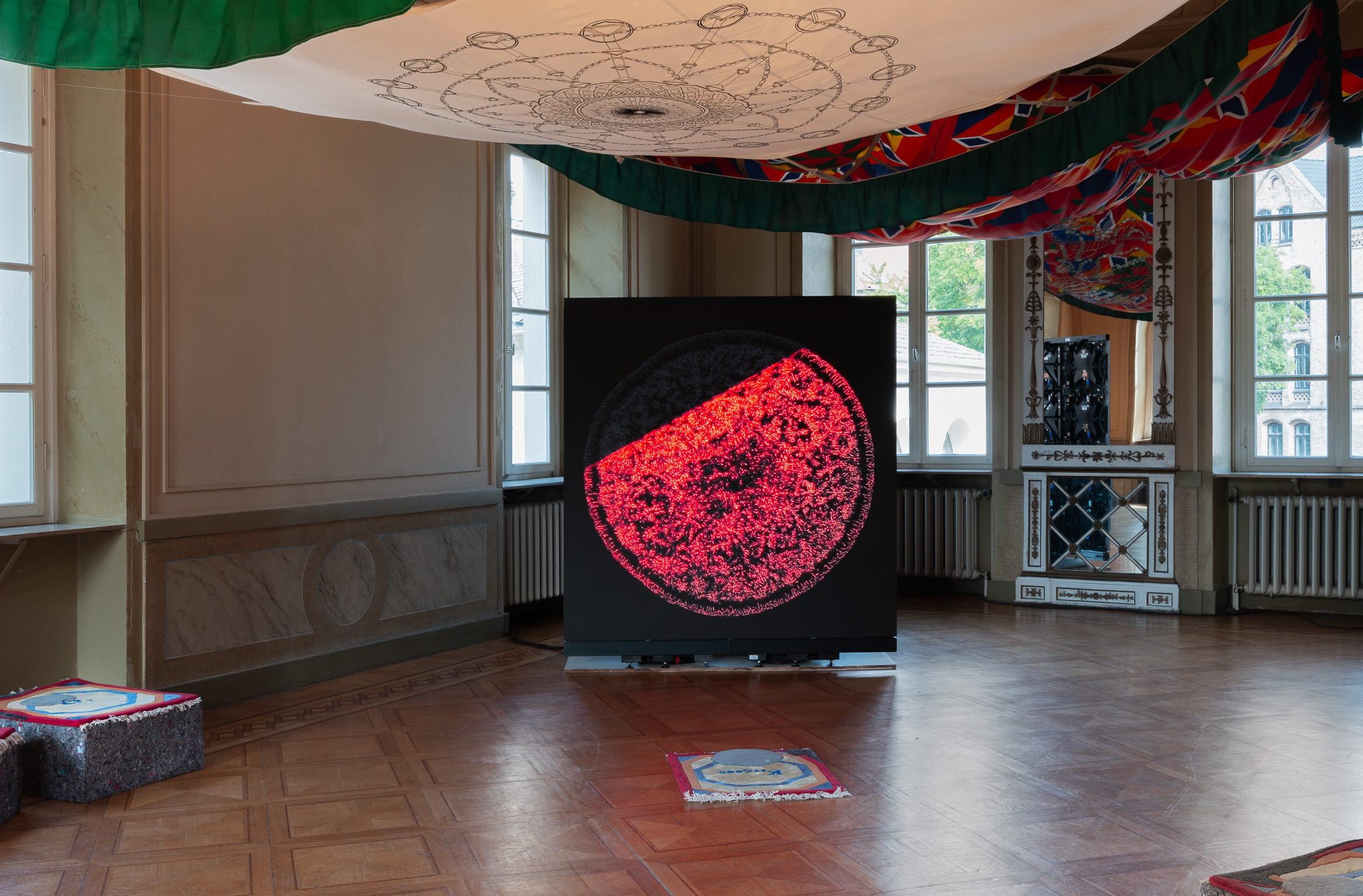

Video loop, LED panel

Duration: 05:59

“Laughter of Tears”, Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany (2021)

An eponymous video loop of the magnification of human tears, including salt crystals in the human teardrop.

Tears are not only for weeping, they lubricate the possibility of vision. Sometimes we see things better when we cry, cry out aloud, or laugh, till the tears come unbidden.

Readymade canopy, radiation hazard sign inscribed as a pattern in salt on the floor (240 x 240 cm)

The Laughter of Tears, Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany (2021)

Every willful misstep, every greedy grab, is an intimate intimidation to our own longer future. How do we stay together, in care of each other, when the fold of our collectivity is augured under the mark of contamination?

“Salt

Many years later on the shores of the Dead Sea, at the lowest and saltiest point on earth, we witnessed another encounter between airplanes and the landscape. A sortie of Israeli Air Force fighter planes flew overhead, breaking the sound barrier as they completed a routine exercise patrol along the Jordanian border. This is the occasion of the second conversation.

It is well known that sound travels faster in saline water. This is due to the face that the bulk modulus (susceptibility of a substance to uniform pressure) of salt water is higher than of sweet water, and since the saltiest water on earth is at the Dead Sea the sound of jets breaking the sound barrier in the air above travels faster in the Dead Sea than it does anywhere else. Not surprisingly, It seemed that day as if the salt crystals in the water were cracking under the enormous and sustained impact of the jets passing overhead. (Salt subjected to the cymatic pressure of high frequency sound waves does disperse at higher rates, so this was not an unwarranted sensation to experience or imagine) That afternoon, the planes defeated the earth around the Dead Sea as they broke the sound barrier, as they must have, every time they flew overhead in search of real or imagined wars. More salt dissolved into the Dead Sea, making it more difficult for water to evaporate, reducing the moisture content of the atmosphere, increasing the thrall of the desert on the land and of the salt in the sea.

With salt, like everything else, the crucial question to ask is how much? ‘How much’ is the most important question in ecology and biology. How much rain? How much nitrogen? How many predators? How much room? How many antigens? How many species? How much food? How many trees of which kind? Normal and healthy processes turn toxic or pathogenic when an element either exceeds beyond or diminishes below its necessary concentration. There is nothing that there cannot be too much of in nature. Ecology is all about balance and concentration.

In the end, we are beings made up of carbon, water and salt. The salt in our bodies is an indication of how much the earth courses through our blood, sweat and tears. But it is also indicative of ratios and proportions. Because the earth and us are made of the same things we can get an instinctive understanding of the question of proportion?

How much salt should there be in the sea? And how much in our tears?”

– Three and a Half Conversations with an Eccentric Planet (2013) Published in Third Text, 27:1, 108-114, DOI: 10.1080/09528822.2013.752233

What does knowledge taste like? The unsalted white of an egg. It asks for the garnish of betrayal. An instruction based work for public libraries which pauses to consider the saline taste of wisdom.

“We thought of the community of readership, which is a silent community. If you go to a library and borrow a book, you see stamps with names of other people who have borrowed the same book. It is like a fellowship of readership. What we are asking you to do is just the opposite of stealing books from a library. It in fact contributes a strange miscegenation of knowledge, a hybridisation of lets say a detective novel and philosophy, the cross-fertilisation of recipe books with books on religion, insertion of pornographic tracts into manuals for mechanics and all sorts of cross-fertilisations that lead to surprises.”

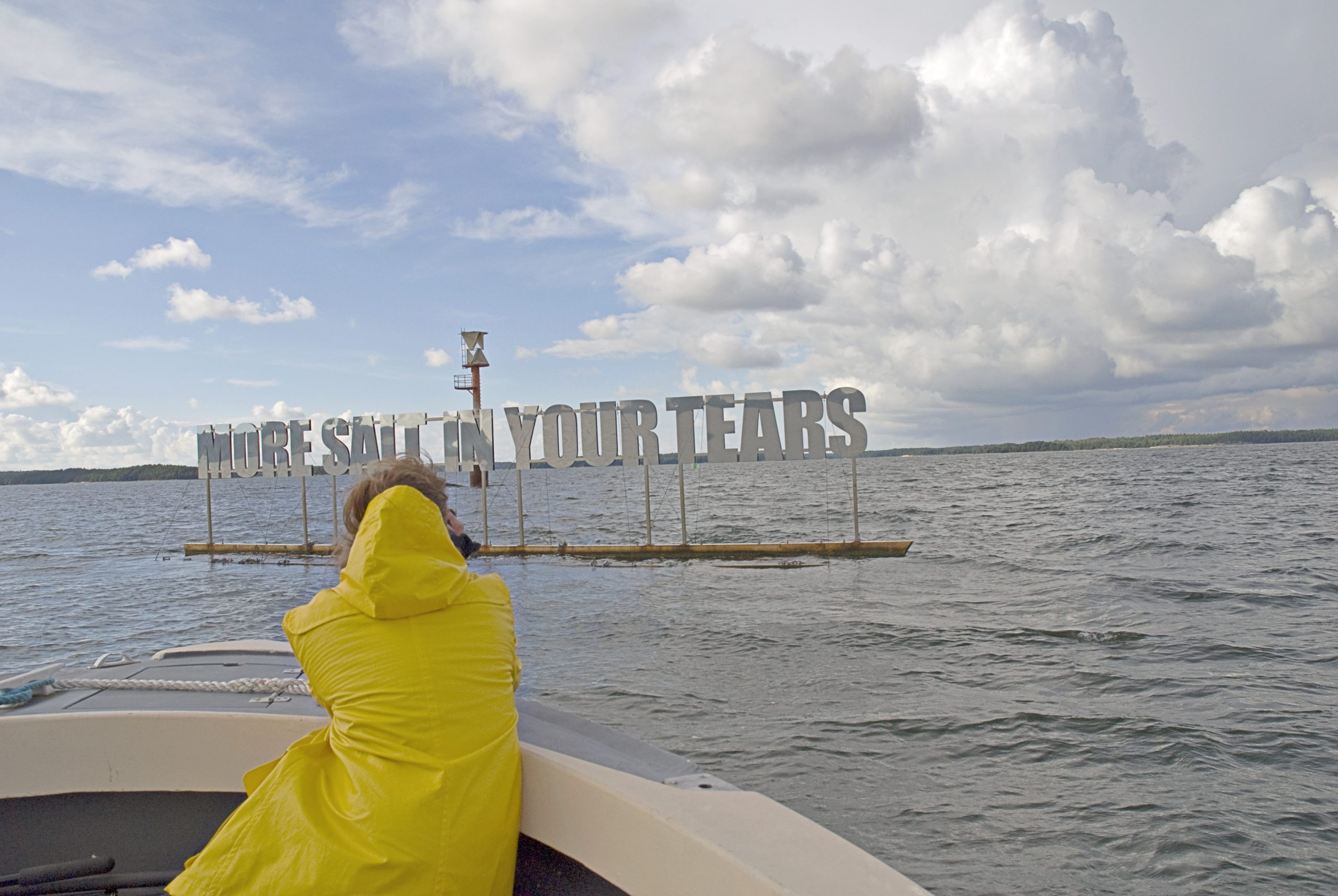

Site-specific installation in the Baltic Sea with stainless steel, steel cable, wood, concrete anchors

Contemporary Art Archipelago, Turku, Finland (2011)

More Salt In Your Tears is a text sculpture composed of three dimensional stainless steel letter-forms anchored on to a shallow section of seabed of the Baltic Sea near Turku, Finland. The letters combine to form a single phrase – More Salt In Your Tears – that can be visible from the decks of passing ferry-boats, ships and low-flying aircraft. With this work we fulfill three specific desires, of writing on water, of connecting body fluids like tears in a precise and intimate way to large natural water bodies and of drawing attention to the ways in which we all respond at a subliminal level to the presence of water. This work continues a pre-occupation with the emotional resonances of marine and coastal landscapes that began with Unusually Adrift From the Coastline (2008), which used the memory of abandoned light-houses to tap into the ineffable quality of our encounters with light, horizons and coastlines by the North Sea.

With More Salt In Your Tears we move into another register, of reading the sea, of weighing tears and tasting the feeling what it means to be close to the sea. Seen at a distance, the work will appear as a reflecting interruption on the water whose shapes also resolve into letters and words. The letter-forms are a set of polished surfaces, gleaming like mirrors as they stand one metre above the water and fifteen metros across the surface of the sea. The forms will mirror the horizon, the sea, reflecting the changing sunlight, and aspects of anything that sails or swims past.The clear surface will change colour as the sea, sky and sunlight themselves vary over the course of the day. In this way, the work will act as an index of the alive, changing surface of the sea, the seasons and time itself.

This is heightened by the startling realization that our tears have more salt than the Baltic Sea. Central to the work is the notion that the Baltic Sea, (which being a virtually inland, river fed water body) has less salinity in comparison to our tears. In recent years, climatologists and oceanographers have expressed the concern that global warming may increase the salinity of the Baltic Sea and by doing so cause irreversible damage to the unique ecosystem of this marine environment. In that sense, More Salt In Your Tears is a paradoxical statement of hope and optimism, for although tears are universally understood to stand in for sad tidings, the day there will be more salt in the Baltic Sea than in our tears will indeed be an occasion for mourning. The hope that there may always be more salt in our tears than in the Baltic Sea is a strong undercurrent of this work.

Bloom

Video (2013), Duration: 2:30 minutes

During Raqs’ visit to the Dead Sea, it was the supersonic booms of a squadron of jets circling overhead that set in motion a creative process revolving around the meaning of salt in various cultural and historical contexts and as a philosophical and metaphysical metaphor. The key concept in this study is the notion of sediment in its metaphorical sense as denoting cultural and linguistic stratification. So, for example, salt appears in such linguistic expressions as “the salt of the earth” and the biblical “salt covenant”, or the Hindi expression Namak Haram (“disloyal to salt”), denoting an untrustworthy person. As a valuable mineral, salt carried crucial significance in economic and geographical networks up to the modern age, and therefore also symbolic significance – for instance, in Gandhi’s Salt March.

The preoccupation with salt carries symbolic meanings that cross cultural boundaries but also change dramatically from place to place – and for this reason serves Raqs well for the purpose of exploring the relations between localism and globalism.

The supersonic booms they heard over the Dead Sea reminded the artists that sound travels faster in saltwater than in freshwater because the bulk modulus – the measure of a substance’s resistance to uniform compression – of saltwater is higher than that of freshwater, and thus that supersonic sound exerts enormous pressure on the salt crystals. The same planes that are supposed to protect the sea and its salt, the artists surmised, could potentially harm it, and it is this ironic reversal of roles that lies at the heart of Raqs’ work and relates to their ongoing meditation on the tension between man and nature.

The Namak Haram’s Philosophy, Revised

Treated Photographic Diptych, 96.6 inches x 24.4 inches

Words, A user’s manual, Gallery 320, New Delhi (2012)

Every book demands another, but not all of them get written. Every debt demands to be paid, but not all are redeemed. Then there are the debts that we owe to the all that we read, which we can never really repay. In that sense we are all namak-harams, defaulters to the debt of purloined knowledge. Someday, a Hamlet will issue a stern reprimand, saying, “There are more things on heaven and earth, namak-haram, than are dreamt of in your philosophy”. He will be reminding us of the things we owe, with interest.

Somewhere, there might exist a library dedicated to the philosophy of the namak haram, stacked high with books filled with the unwritten word. What titles would one browse if one came across its stacks, folded into the course of a tiring day like a mirage in a desert? Can books be desired into existence by reciting the spells that are waiting to be read off the surfaces of their wished-for spines? Can the Namak Haram ever repay his debts, with interest?

“The Philosophy of the Namak-Haram” is a work that speaks to bibliophilia, day-dreams, intellectual debt (which doesn’t yet have lawyers, unlike intellectual property) and the pleasures of book-binding. The treasures its invokes are always waiting to be read.