A Day in the Life of Kiribati

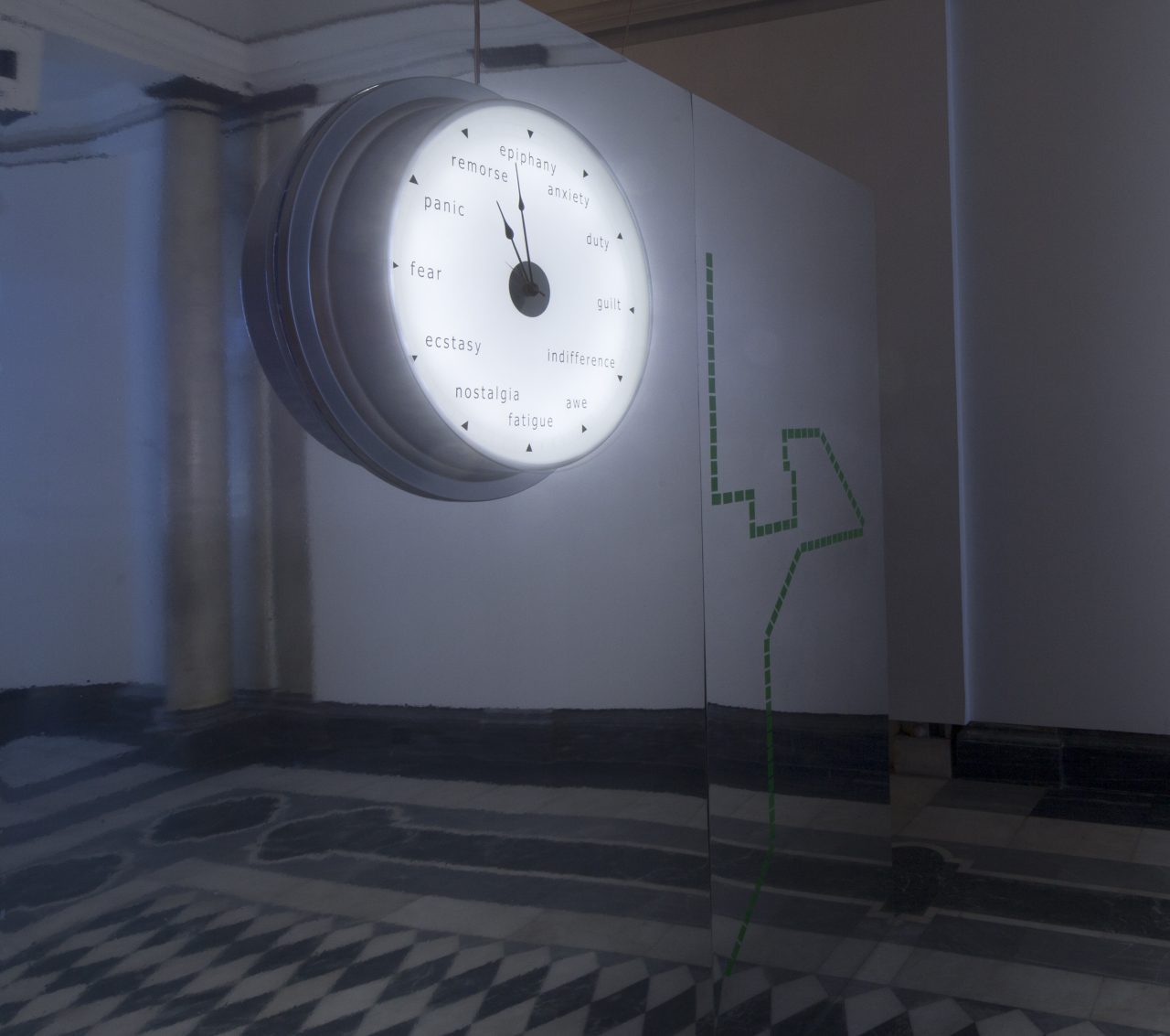

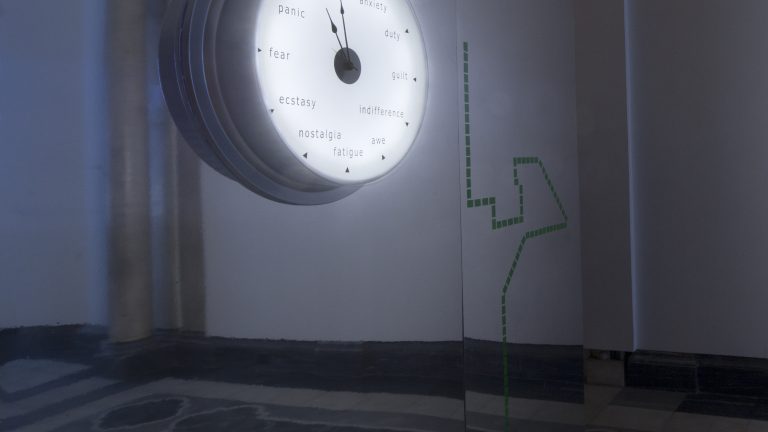

Shown at: ‘Untimely Calendar’, National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi (2014)| ‘From the Cosmos to the Commons’, Stadtkuratorin Hamburg (2025)

Clock, nameplate, tape

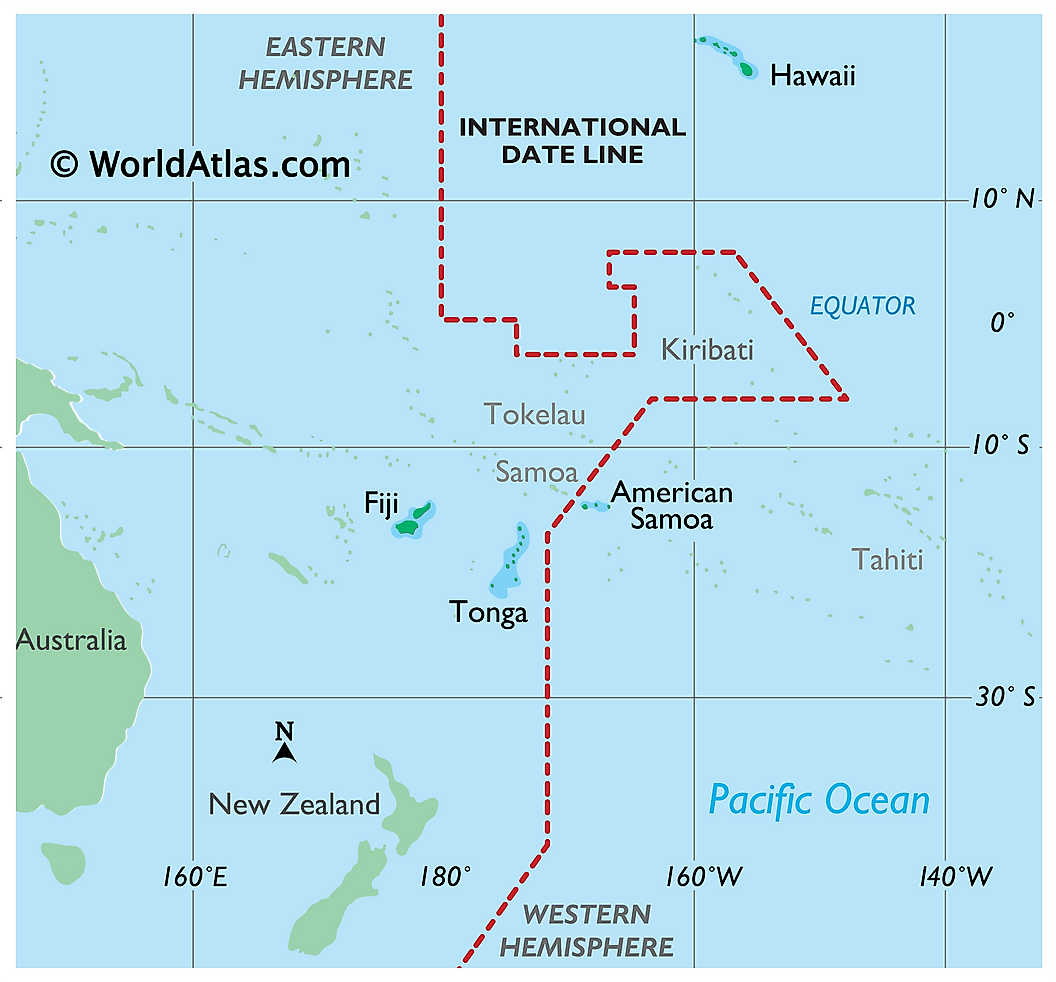

A Day in the Life of Kiribati shows the current time in Kiribati, an island nation in the Pacific twhich bended the imaginary line of meridian to stay in the local time zone. It is also the first land on Earth to switch the calendar over to 2000, and which could be the first place on this planet to disappear with rising sea levels because of global warming. Here, timekeeping becomes both a marker of continuity and a reminder of impermanence.

Raqs sets this clock ticking in contrast to the measured precision of modern timekeeping, which splits past from present, here from elsewhere. The work reminds us that while time appears uniform, London and Lagos may share a time zone, our lived experiences of “now” are shaped by geography, politics, and climate. This disjunction makes “now” feel distant from “then” and yet, paradoxically, connects disparate places under a shared measure of time. In a syncopated sort of way, we are contemporaneous with other times and spaces. In Kiribati, time is not only a way to mark continuity, but a fragile measure of what may soon be lost.