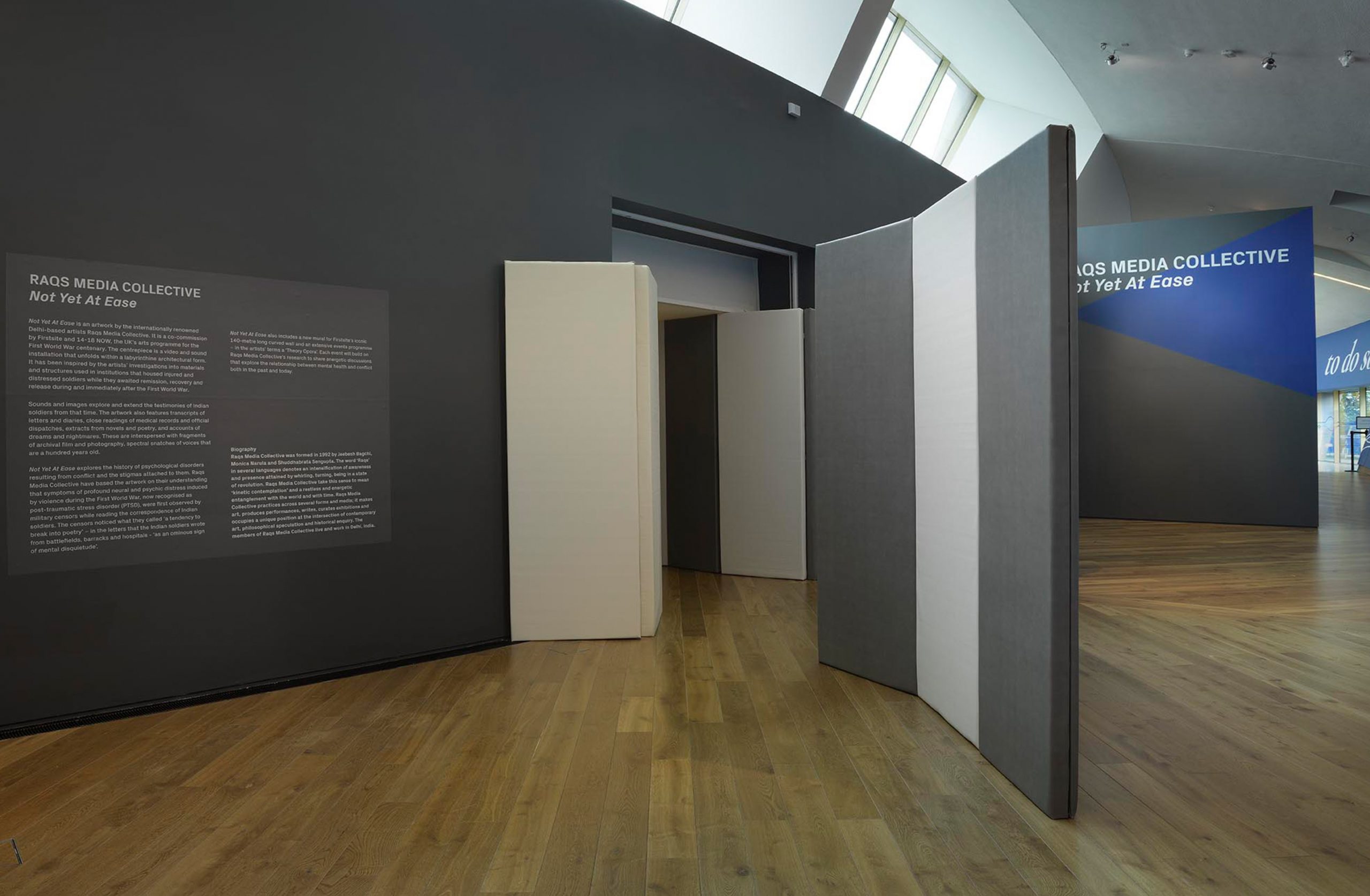

Not Yet At Ease

Solo Exhibition

FirstSite, Colchester, United Kingdom (2018) | ‘Spinal’, Frith Street Gallery, London, United Kingdom (2019)

Not Yet At Ease marks the centenary of the First World War by speculating that – in some crucial ways – the First World War never ended. In many territories that were once battlefields of the First World War, especially in Eastern Europe and in West Asia, the world still stands just as uneasy and volatile. The ghosts of dead empires and the shadows of their armies have not yet left the battlefield. There is a lingering unease.

Not Yet At Ease premiered at FirstSite, Colchester as part of the 1914-18 Now Commissions: a series of new artistic works commemorating a century of the First World War.

The work builds a labyrinth evoking the maze of the trenches, but with materials that echo the padded walls of hospital cells where ‘shell shocked’, sick, and injured soldiers were confined while undergoing treatment. Within this labyrinth films, voices, images, poetry, officialese and reportage jostle for attention. Not Yet At Ease mines archival resources and invents a dreamscape to build a lyrical and imaginative layer of reflection. It discovers and highlights the official discomfiture with the “excess of poetry” that the soldiers were writing home as a sign of ‘mental disquietude’). This is an early admission, which is also, simultaneously, an evasion, of the psychological distress produced by war.

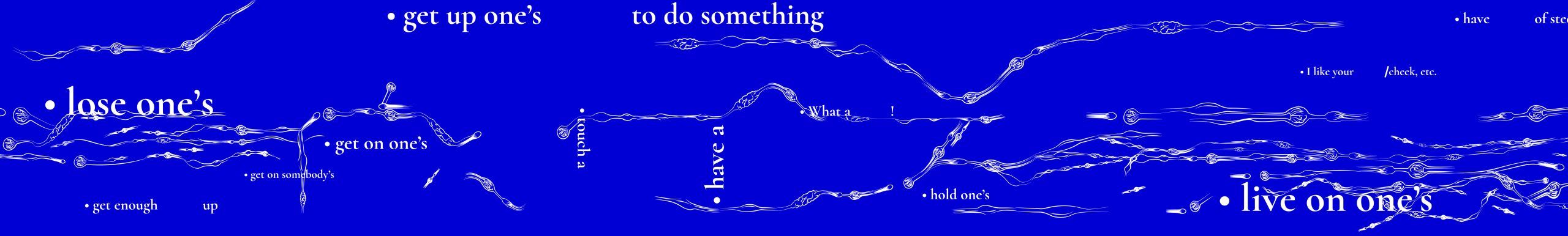

Mural, Text and Drawings transferred in Vinyl

140 meter long curving wall

The bold blue colour that forms the ground of Nerves is inspired by the Hospital Blues uniform worn by convalescing soldiers in British military hospitals in the early twentieth century. This intense colour field is overlaid with drawings of nerves and nerve endings as they were understood in 1916. The text fragments are phrases and expressions that use the word “nerve”, though the word itself is removed. English has many aphorisms around nerves: “a bag of nerves”, a “battle of nerves”, “a war of nerves”, “nerves of steel”… This gesture creates an abstract, almost code-like pattern that viewers can decipher, and acts as an analogue for the frayed consciousnesses produced by shell-shock on the battlefield.

Video

Duration, 10′ 24″

Spinal is a study of the vertebral column that brings together an anatomical model and a dancer’s body in a conversation of gestures, stances, steps, positions, and caresses. The positions traced by the dancer’s body echo the arrangement in John Singer Sargent’s iconic 1912 painting “Gassed”, where a line of wounded soldiers, blinded by a nerve gas attack, hold on to each other, shuffling towards an uncertain goal. Hovering, too, is an image of the dancer’s hands caressing a pedagogical model of the human back-bone.

This exchange references the silences and elisions to avoid the term ‘shell shock’ (which has evolved to become PTSD today) by British Military Authorities. The “nervous ailment” – which authorities claimed was only experienced by officers and not British soldiers, or soldiers imported from other parts of Empire – was said to be linked to ‘disturbances in the spinal column’ caused by repeated vibrations from gunfire and bomb explosions.

Spinal attends to early twentieth century’s dislocations as a move towards understanding human fragility and endurance.

(email us on studio@raqsmediacollective.net to request access)

Looped Video

Duration, 2′ 47″

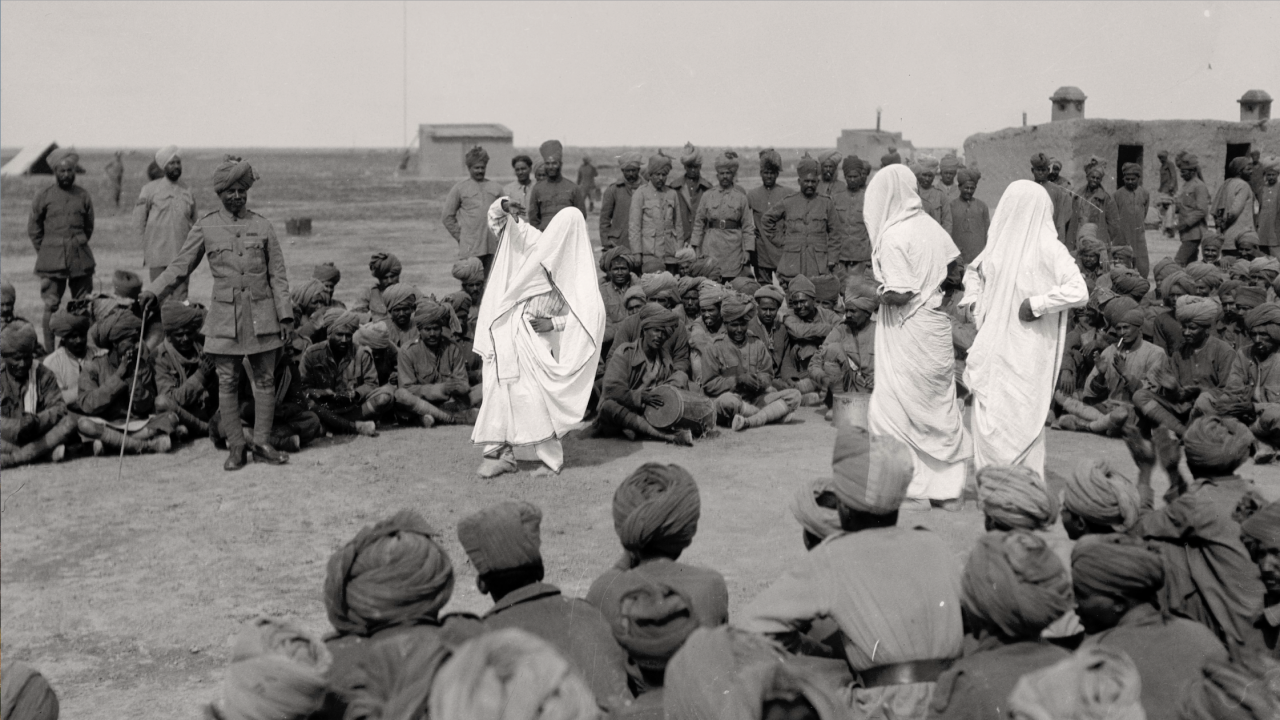

A photograph labeled ‘Indian Porter Corps open theatre at Kut’ in the Imperial War Museum Archives depicts three figures shrouded in white, dancing for a group of men seated in an open field. A Sergeant or officer stands with a cane, in the upper right hand corner of the frame. The performers, and the majority of the men, are porters – members of the Indian Labour Corps, an often forgotten part of the Military as they performed the enormous menial labour of keeping millions of soldiers and their horses fed, the dead removed, and camp set up. In Three Shadows, these dancing figures in white have been isolated to present them as ghostly spinning spectres.

Ghosts abounded in the letters that soldiers sent home, and the Great War’s ghosts haunt us still.

Iteration shown at: Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany (2021)

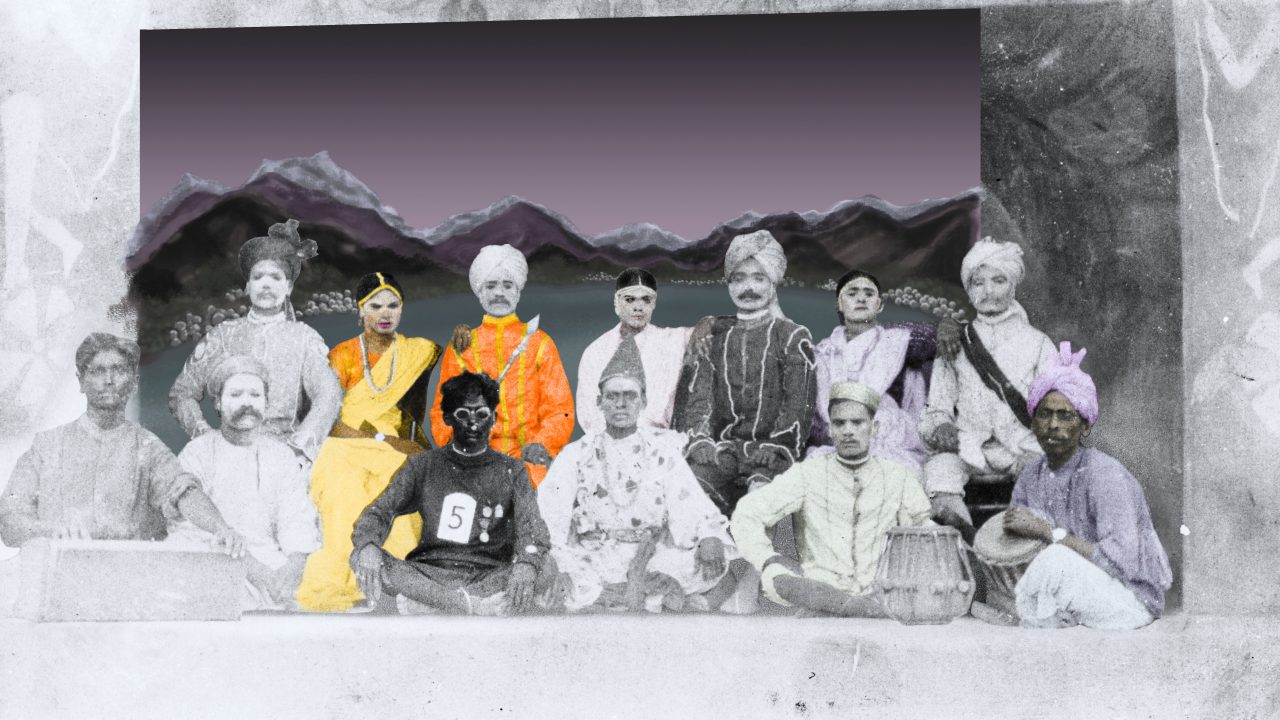

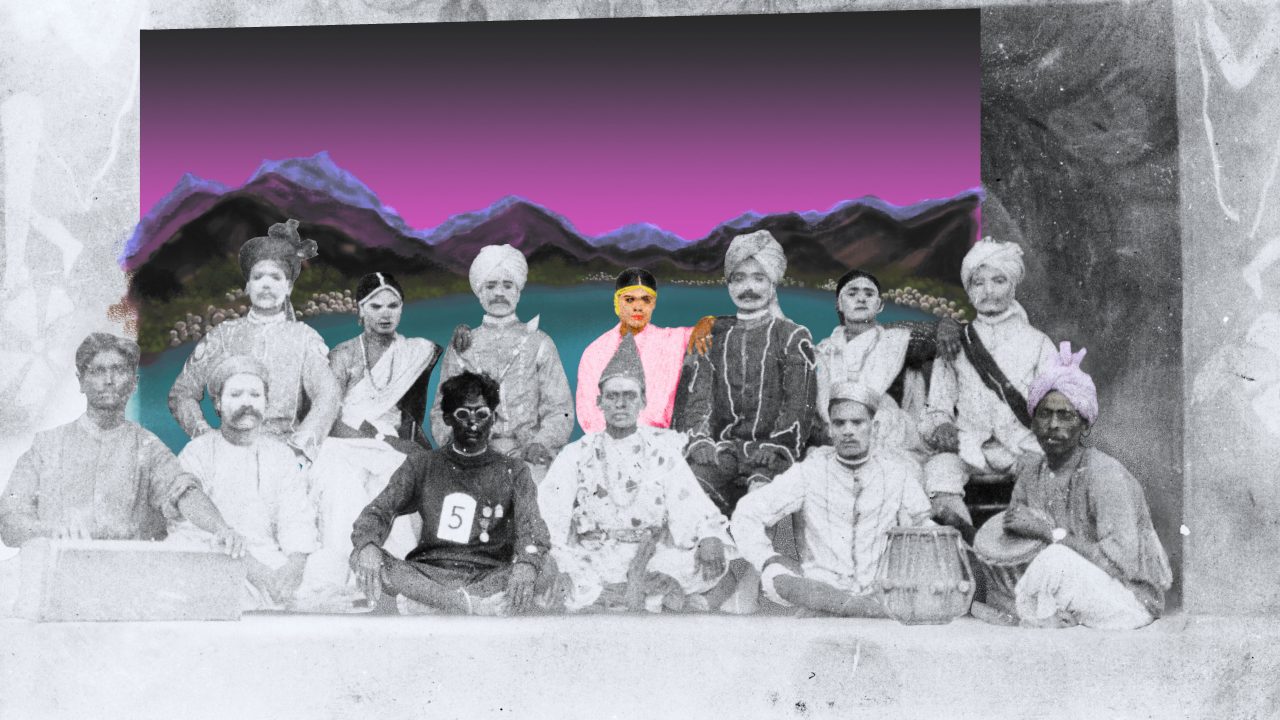

Group Photo

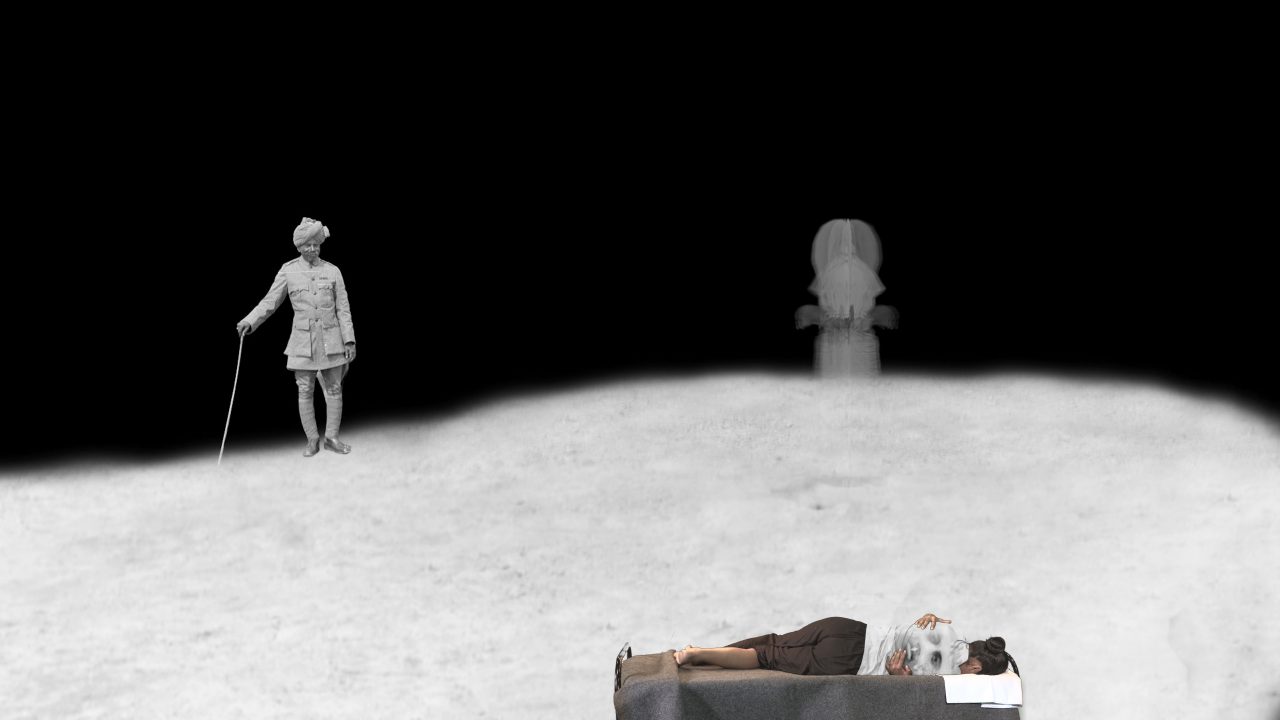

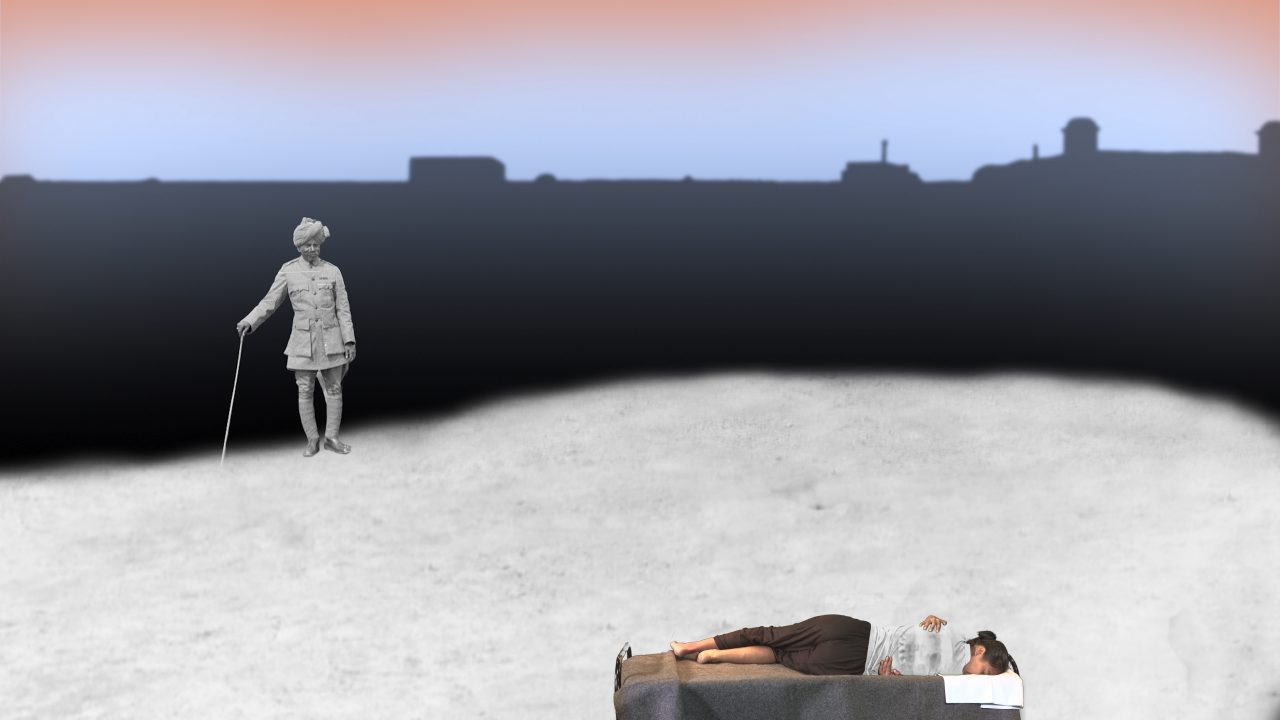

Looped Video

Duration, 2′

Performers of an Indian concert party at the Royal Ordnance Corps theatre, Baghdad, ca.1917 is a posed group photograph of a troupe of Indian soldiers and non-combatants near Baghdad, in the Mesopotamia theatre. It is possible that this is a photograph taken during a celebration of a religious holiday. Some of the performers, including the female impersonators, have their faces whitened with flour. A note on the reverse of the original photograph states that the performance lasted from 8pm until 3.30am. Musical accompaniment was provided by tom-tom drums and the small box organ seen on the left of the photograph. In Group Photo, this image has been animated to suggest the appearance and disappearance of colour in the faces and costumes of the performers, and also in the painted backdrop that they are pictured against. This is in keeping with the tradition of hand-colouring of photographs that was a very common feature of photographic practice in India at the time. The colours are indicative of the desire for liveliness in a difficult and drab terrain, and the vivid colours in the landscape are suggestive of the aesthetic of the ‘painted backdrop’ that was common both to folk theatre and to popular photography at the time.

These tropes suggest the ways in which many of the Indian soldiers and ‘followers’ made the conditions of war time ‘bearable’ and lived through very difficult conditions with courage, sensitivity and a sign that they had not forgotten what made life beautiful. This attitude is evident in the letters they wrote home, some of which have also made their way into the audio elements of the work.

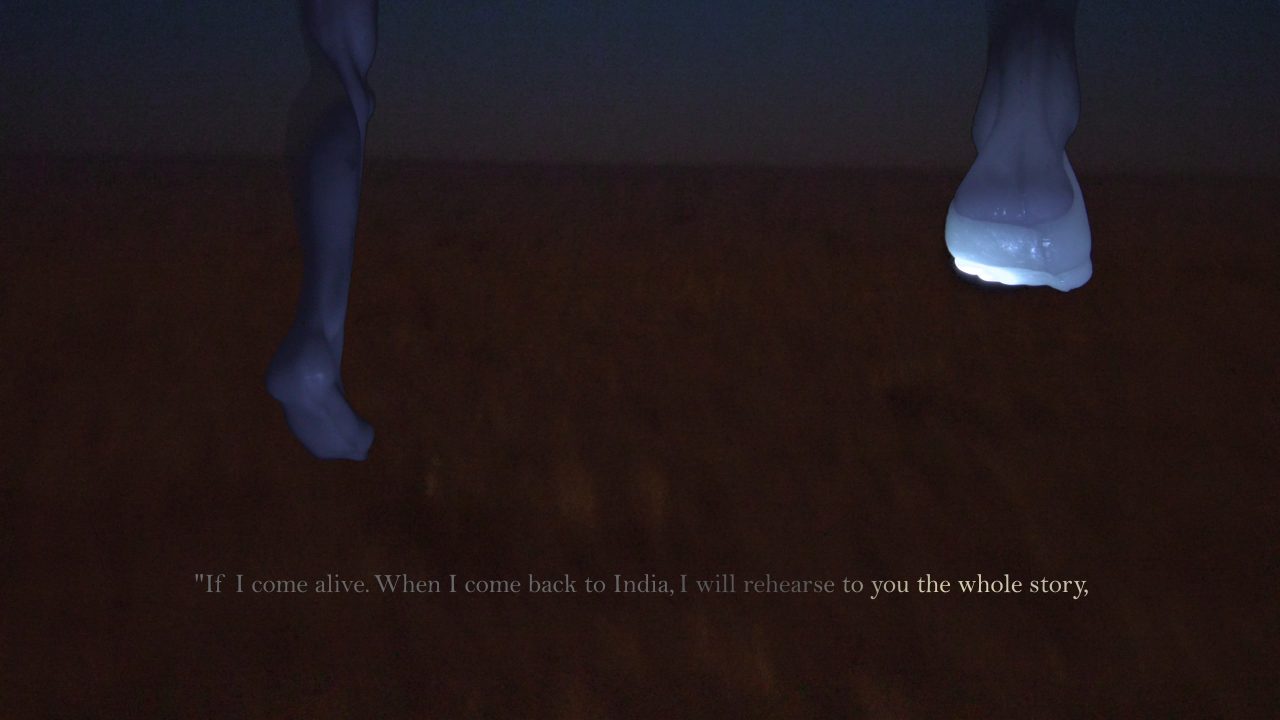

Ghost Floating Legs

Video

Duration, 6’3″

The First World War produced the greatest number of amputated limbs, especially when soldiers lost arms and legs as a result of stepping on mines. These bodies without limbs, and limbs without bodies, became ‘phantoms’ for each other, especially when recovering soldiers continued to complain of aches and itches in the limbs that were no longer attached to their bodies, producing a neurological (and in some senses, spiritual and phenomenological) puzzle that would fox scientists and doctors for a long time.

Ghost Floating Legs is an exercise in the invocation of these phantom limbs and their absent presence on the skin and soul of time.