Still More World

Solo Exhibition

Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha (2019)

Still More World confronts the thresholds of sustainability and to consider what futures we might illuminate—or extinguish—in our quest to shape the world. It is a delicate interplay between the material and immaterial, reminding us that every illuminated skyline carries within it echoes of unseen histories and latent possibilities. Raqs continues its inquiry into the immeasurable, the exhibition embodies the paradox of our era—where the relentless pursuit of growth coexists with the urgent question of how much more the earth can yield.

The exhibition reflects on the luminous energy that animates Doha’s urban landscape—a dynamic stage where light, people, and raw materials converge in a vibrant dance of constant transformation. Raqs draws upon literary narratives and scientific insights to unravel the intricate cycles of progress and change. The exhibition traces the movement of populations across time and space, juxtaposing the material with the imagined, the visible with the felt, and the fleeting with the enduring.

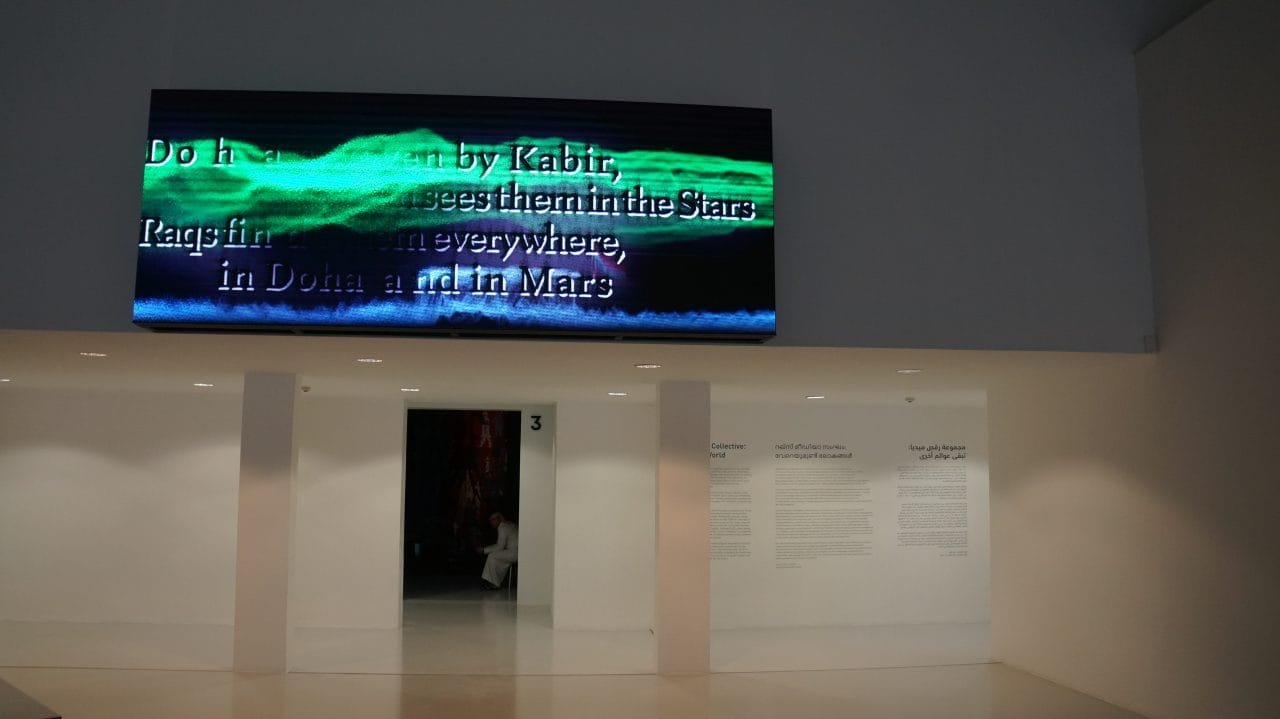

Dohas for Doha

Five Videos, LED screens, variable dimensions

Dohas woven by Kabir,

Rahim sees them in the Stars

Raqs finds them everywhere,

in Doha and in Mars

This doha talks in shadow speech

Where words fail Raqs, let commas reach

When nothing else will do, then Raqs

Try a line or two of madness,

which is but sanity, redux

The video works Dohas for Doha present illuminated proverbs that play with language, light, and the transmission of knowledge. A doha is a poetic form of four-line verses, popularized by the medieval Hindi poet and mystic Kabir. By shifting sequences of words, these dohas create multiple meanings and linguistic puns, engaging in a poetic interplay between the city of Doha and Raqs. The word doha in Hindi also means ‘double,’ offering another layer of resonance.

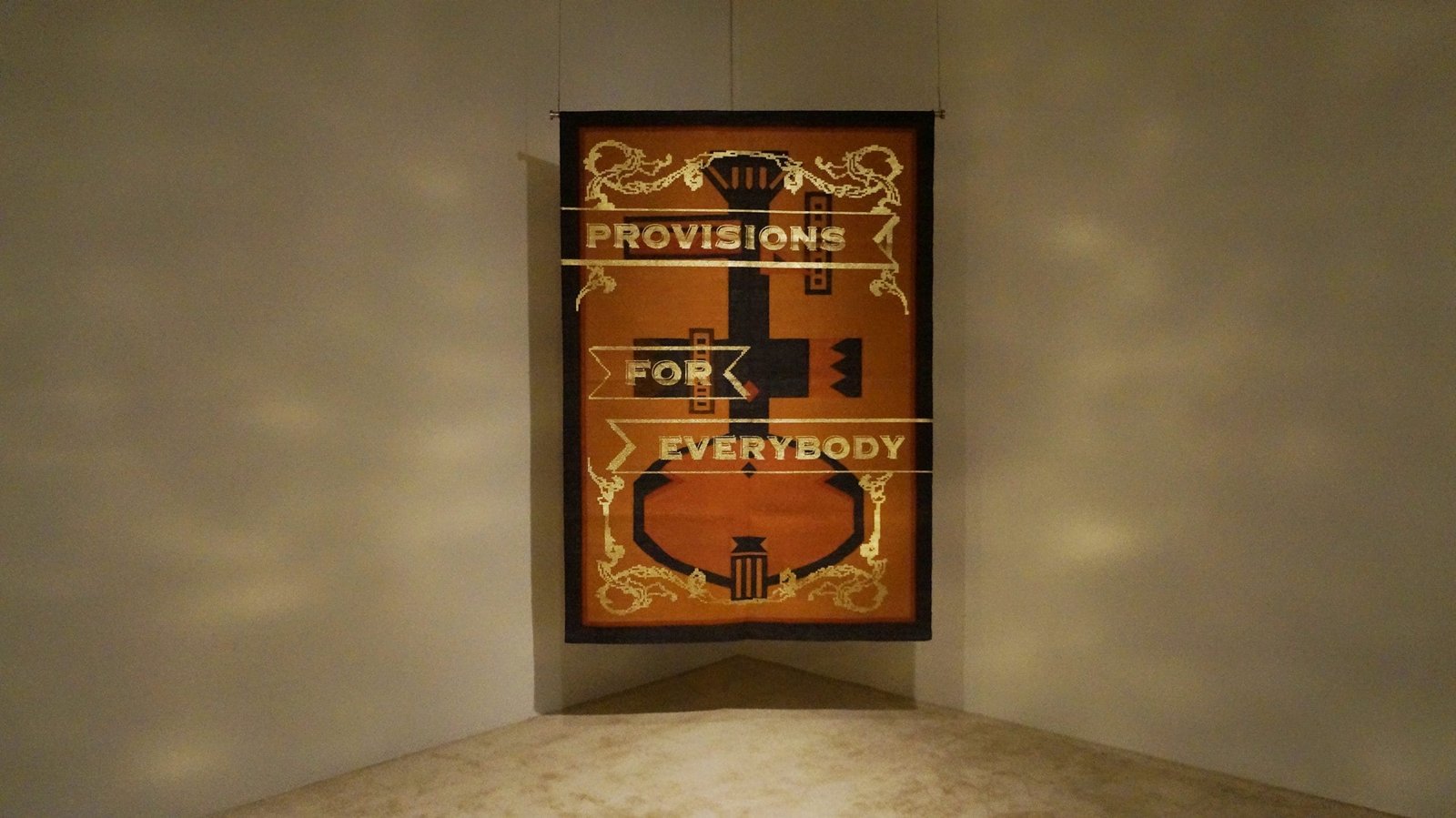

Provisions for Everybody

Installation with 3 Videos, large drawing print, 3 dhurrie banners, drawings on vinyl, found furniture

“Coal Mine. Windmill. Sugarcane Field. Words. Pictures. Memes. It’s all about energy; everything is burning.”

This installation navigates histories of energy and extraction, journeying through sites shaped by coal, wind, and sugarcane. The eponymous video follows an itinerary reminiscent of George Orwell’s travels—tracing shadows of places from Northern England to Eastern India, Myanmar, and Catalonia. Raqs’ journey takes them to Orwell’s birthplace in Motihari, Bihar in Eastern India, where they consider his assertion – “to abolish class – (and caste)- distinctions means abolishing a part of yourself” in tandem with the Buddha’s celebration of doubt, which happened more than two millennia ago, in the same neighborhood. Accompanying videos, A Planet Turns on its Axis Without Permission and Things to Look at and Reconsider, further explore themes of time, revolution, and remembrance. Suspended dhurrie banners titled Let the Future Praise Us reference historical labor movements, weaving together images, texts, and textures to invite new ways of thinking about potential and plenitude.

Iteration shown at: AV Festival, Newcastle (2018)

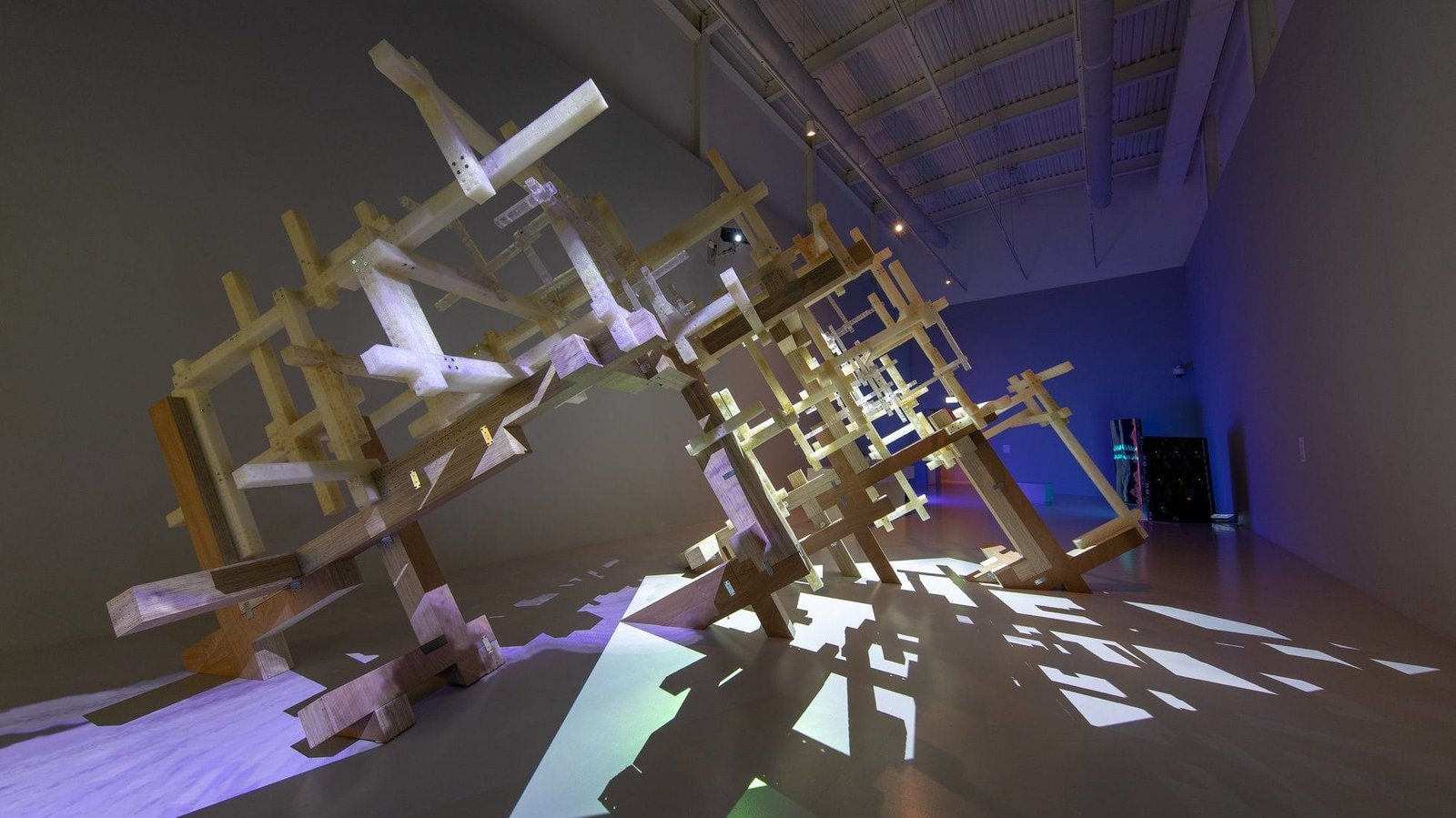

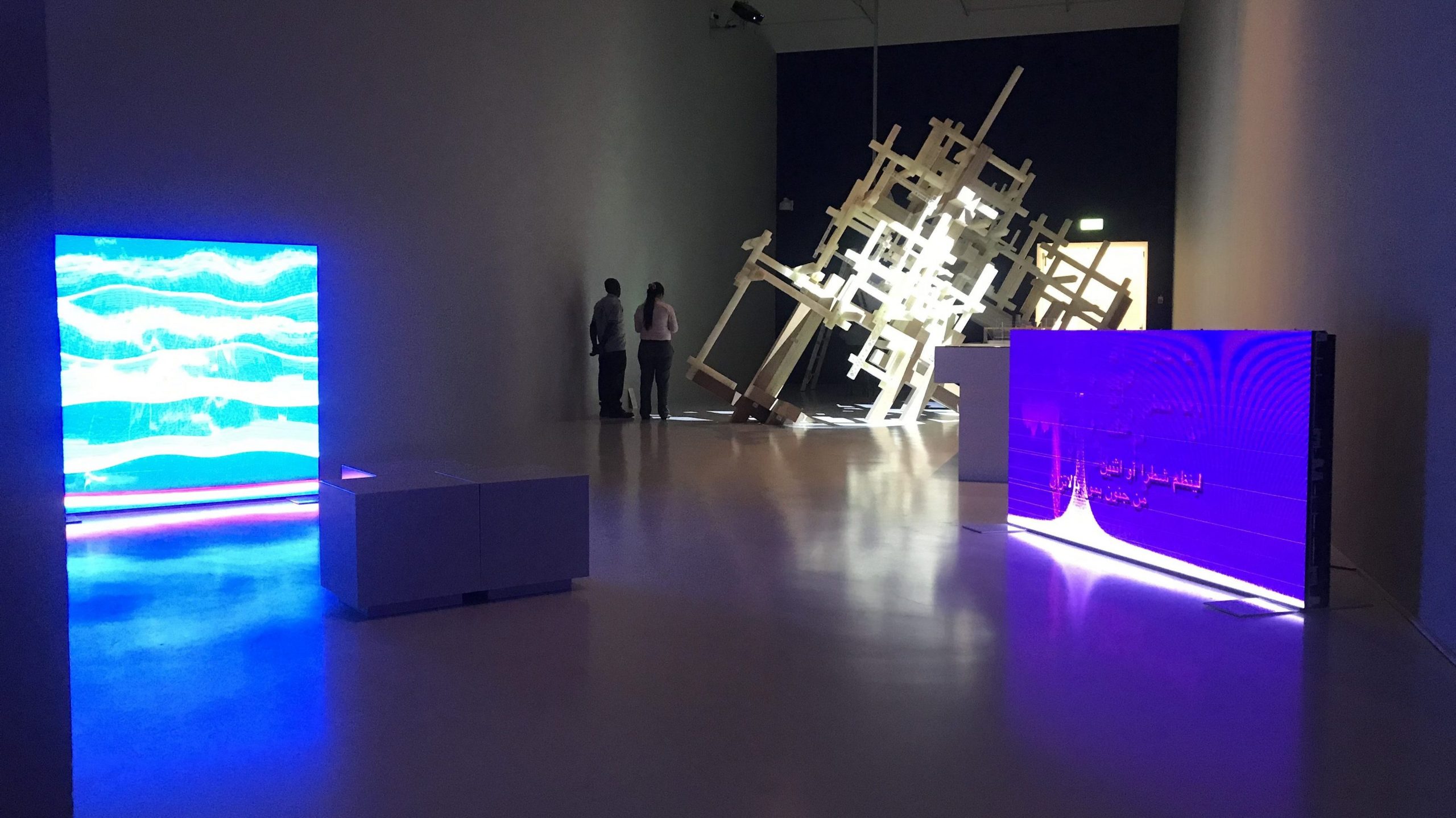

Alive, with Cerussite and Peppered Moth

3D printed PLA plastic, cast polyester resin, plywood and video projections Dimensions variable

Architectural Collaborators: Palak Jhunjhunwala and Stratis Georgiu

This architectural installation speaks to the evolution of materials and living forms across alternative time epochs. The 3D printed structure represents crystal cerussite ,while the light projections refer to the changing colorations of the peppered moth that occurred during the industrial revolution. At the beginning of the age, the black and white peppered moth experienced industrial melanism – its pigment became black for better camouflage in an environment polluted with soot residues. This evolutionary strategy was reversed when pollution levels were reduced. These varied states of transformation speak to changing invisible threads of ecology, and compressed time.

Iteration shown at: The Whitworth, Manchester (2017) | Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2020) | The work is now in the permanent collection of Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art , Doha.

The Untold Intimacy of Digits

Looped video projection

Duration, 47“

In every sum figured by power, a remainder haunts the calculation. Not everything adds up. A people are never equal to a listing of their bodies. They are something more and something less than a population. Counting counter to the reasons of state, Raj Konai, a peasant from nineteenth century Bengal, the owner of the floating trace of a disembodied hand indexed in a distant archive, persists in his arithmetic. The handprint of Raj Konai was taken in 1858 under the orders of William Herschel – scientist, statistician, and at the time, a revenue official with the Bengal government. It was sent by Herschel to Francis Galton, a London eugenicist and pioneer of identification technologies. It is currently in the custody of the Francis Galton Collection of the University College of London. This is where the Raqs collective first encountered the image of Raj Konai’s hand. Fingerprinting experiments, and later technologies, all began with this handprint. India has now embarked on a nationwide Unique Identification Database (UID) and plans to have its billion soon counted and indexed.

Iterations shown at: Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi (2011)| Art Gallery of York University, Toronto (2011) | Museum fur Moderne Kunst (MMK), Frankfurt (2012) | National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi (2014) | K21, Düsseldorf (2018)

To People

11 Textile and 2 Prints on paper

100 x 500 cm each

A series of handwoven carpets and paper prints cascade through the gallery, depicting figures as interwoven forms—collectives, networks, and the act of ‘peopling’ a space. The work explores the meaning of the verb ‘to people’, which can suggest populating and inhabiting a space, wilfully or enforced, but can also be read as a work that is ‘for people’, referring to one person or multiple individuals.

The pixelated figures create a modular, blurred landscape of objects and human forms in transition. Together the carpets constitute one image of the nexus of people coming together in large urban cities. The pixelated silhouettes evoke movement, transition, and the densities of urban life, reflecting the diverse inhabitants of Doha and the broad networks they create.

Spinal

Video

Duration, 10′ 24″

Spinal is a study of the vertebral column that brings together an anatomical model and a dancer’s body in a conversation of gestures, stances, steps, positions, and caresses. The positions traced by the dancer’s body echo the arrangement in John Singer Sargent’s iconic 1912 painting “Gassed”, where a line of wounded soldiers, blinded by a nerve gas attack, hold on to each other, shuffling towards an uncertain goal. Hovering, too, is an image of the dancer’s hands caressing a pedagogical model of the human back-bone.

This exchange references the silences and elisions to avoid the term ‘shell shock’ (which has evolved to become PTSD today) by British Military Authorities. The “nervous ailment” – which authorities claimed was only experienced by officers and not British soldiers, or soldiers imported from other parts of Empire – was said to be linked to ‘disturbances in the spinal column’ caused by repeated vibrations from gunfire and bomb explosions.

Spinal attends to early twentieth century’s dislocations as a move towards understanding human fragility and endurance.

Iterations shown at: FirstSite, Colchester, United Kingdom (2018) | Frith Street Gallery, London, United Kingdom (2019)

Seven Billion and One

Variations of the infinity sign in gold pigment, on pages of newspapers coated with black ink (English, Hindi, Urdu)

108 sheets of 22 x 14.5 inches

The seven billion people of the planet are animated today as they have never been before — with possibilities, propositional forms, and with an entirely new morphology and vocabulary of solidarity. There is an infinity of infinite possibilities. This takes the form of a recognition of abundance and a sense of infinite plenitude in everyday life, in a million mutinies, that translate into occurrences, co-incidences and resistances. We are in a time of kairos, not chaos — of the seizing and transformation of time.

Iteration shown at: School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (2015)

The Translator’s Silence

Three lenticular panels

22 inches x 36.6 inches each

When familiarity breeds only contempt or indifference, the hope for solidarity lies in the kindness of strangers. The subtle ties between “host,” “hostility,” and “hospitality” frame this inquiry.

As Faiz Ahmed Faiz writes, “How many meetings will it take for us to embrace one another again?/ What fear have I of strangers, the cup of life will fill by knowing the unknown.” Rabindranath Tagore inquires, “what fear have I of strangers,

the cup of life will fill by knowing the unknown?” Meanwhile, Agha Shahid Ali inquires,“Will you, beloved stranger, ever witness Shahid—two destinies at last reconciled by exiles?”

The care of strangers is the gentlest and the sharpest form of sedition. In regions marked by names like India, Pakistan, and Kashmir—each a state of quarantine—familiarity often breeds contempt. Yet the prospect of future mutuality in our strangeness offers a hopeful alternative, where lingering questions pave the way for understanding.

Drawing on these insights, this work suggests that a stranger can become beloved when adversarial destinies—common in the fractured histories of partitions and lines of control—are reconciled through a willing encounter with the unknown in the other. Such encounters, spanning languages, memories, desires, and nightmares, may initially render us speechless. Perhaps in that silence, we find the means to translate each other’s unspoken truths—a delicate pause that becomes a gift.

English, Bengali and Urdu/Hindustani are the primary working languages of the three members of the Raqs Media Collective; translation is their mother-tongue

Iterations shown at: Shown at: Purdy Hicks Gallery, London (2017) | Gallery 400, University of Illinois, Chicago (2017)

36 Planes of Emotions

Laser engraved acrylic glass, furniture, lighting (180 x 150 x 60 cm)

Graphic design: Amitabh Kumar + Satyabrata Rai

This work plays with the idea that human experience is not singular, but layered. 36 descriptive phrases describe feelings that cannot be reduced to a single word, to evoke the complexity of emotions such as joy, fear, love and sadness, as experiences that impact the state of the brain and heart differently for every individual.

These phrases were formed with the thinking about how a person or a body inhabits a feeling that emerges in the context of different experiences and situations. Raqs describes this practice as exploring the ‘spectrum of unrecognised possibilities’. Rereading the phrases as book titles on plexiglass suggests the possibility of transparency, as complexity of emotion is revealed in a way that a single abstract noun cannot do.

Iterations shown at: Art Gallery of York University, Toronto (2011) | The Photographers’ Gallery, London (2012) | The Whitworth, Manchester (2017) |K21, Düsseldorf (2018)